Economist, Dr Anthony Ockwell recently worked with cardiac arrest survivor, Greg Page’s Heart of the Nation to calculate the cost of sudden cardiac death in Australia.

Dr Ockwell’s modelling showed that the economic cost of sudden cardiac arrest to Australian society is AU$51.2 billion per year. This astronomical figure was calculated by determining the value of lives prematurely lost, demonstrating what Australian society stands to gain economically if the sudden cardiac arrest survival rate can be improved.

The following is an edited transcript of our recent conversation with Dr Ockwell, who is founder and director of Economic Connections. Dr Ockwell and his team donated their time, expertise and modelling pro bono to Heart of the Nation.

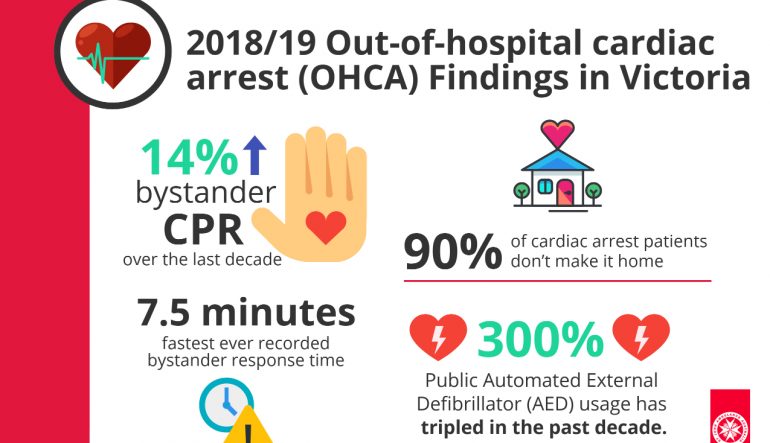

Image credit: St John Ambulance Victoria

My name is Anthony Ockwell. I’m an economist. I have a Bachelor of Science in Agriculture degree with Honours in agricultural economics from the University of Sydney. I also have a doctorate in agricultural finance from the University of Sydney.

I have worked extensively in road safety both in Australia and overseas, and was responsible for the road safety program at the OECD for many years.

Part of our work on road safety is in trying to formulate policies to reduce the number of fatalities, and of course the associated number of serious injuries.

As part of that, in terms of a government policy, it’s important to understand how many fatalities we have. What are the contributing factors to those fatalities? What is the economic cost of, and what it means to the individuals, the families, and of course society? How does this impact government budgets?

That methodology has been around for some years.

One of the key points of that methodology has been trying to estimate years of life lost, and hence the associated loss in productivity.

It also considers the emotional impacts on families, and what that means for lifestyle, both for the survivors of serious crashes and for the families themselves.

Obviously, if a person is seriously injured, there is a major loss in productivity and income earning potential, which therefore has those serious ramifications on the future of that family associated with their loved one who has been injured in a crash.

How does this relate to sudden cardiac arrest?

That was the background to Greg Page contacting me, to ask if our road safety research methodology could be applied to better understand the cost and enormity of fatalities associated with sudden cardiac arrest.

Greg Page, as many of you would know and appreciate, is the former Yellow Wiggle who suffered a cardiac arrest on stage some eighteen months, two years ago.

We agreed to donate our time and expertise to develop a better understanding of the impact of cardiac arrest, and help Greg raise awareness of the importance of the Chain of Survival.”

What were some of your initial challenges?

We have little understanding of the enormity of the number of people affected, and the economic cost.

With that in mind, we set out to find a better estimate of the number of fatalities and from there, try to determine the economic cost.

We do have a good data source, which is the out-of-hospital cardiac arrest registry.

On a jurisdictional basis, there are good data. The problem is when you come to try to estimate the impact for Australia.

We had to compare different years of collection, different approaches to collection, the differences between a financial year and a calendar year – and of course, some States not having any data collections whatsoever.

How did you get started?

Our starting point was the Victorian out-of-hospital cardiac arrest registry (pictured) for 2017/18.

This was a very comprehensive data set, that had been used previously by Professor Liz Paratz in her work (at the Baker Heart and Diabetes Institute) to estimate the health and economic impacts of sudden cardiac arrest.

Professor Paratz looked at the five years immediately following a cardiac arrest. What’s the loss in productivity? What’s the loss in income and therefore, how do we deal with that in terms of care and of course, family support?

By comparison, we looked at the economic cost of lives lost to sudden cardiac arrest.

We have a large number of fatalities, but we only have something like a twelve per cent survival rate for people who suffer a sudden cardiac arrest. That’s huge.

The cardiac arrest registry data gives us estimates of incidents, and fatalities. It shows there is no age group that is immune to sudden cardiac arrest. It covers the whole spectrum.

That’s an important point in terms of the life years lost.

What are we talking about in terms of life years lost? For a male, the expected life expectancy is around 81 years. So, if a fellow dies at 40 as a result of cardiac arrest, the loss is roughly 41 years.

What’s that worth? What’s that worth in terms of loss in productivity, the impact on the household, the emotional upset? How do we estimate the economic value of life he has lost?

With our model, you repeat this calculation for all the age groups from under 15 right through to over 75, working out the discounted value to estimate the total cost of each life lost.

Despite the State-by-State data challenges, what we did have was fairly good data on incidence rates.

Basically, the number of incidents nationally was around to 25,700 per year, with a fatality rate of roughly 88 per cent.

That equates to around 22,700 fatalities annually. That’s what we’re dealing with. That’s a huge cost on society. It’s a huge cost on families.

What is the economic cost of sudden cardiac death to Australia?

Our work led us to an estimated economic cost of those fatalities of AU$ 51.2 billion to Australian society.

That is a huge figure.

In contrast, the economic cost of road trauma for that same period was around AU$23 billion.

Just to try and put it into perspective, that figure of AU$51.2 billion represents around 2.5 per cent of Australia’s GDP.

What can we do about this?

This brings us back to Greg Page. Greg’s life was effectively saved through the very quick action of bystanders, the application of CPR, and application of a defibrillator, which was by the stage where he collapsed.

So, how do we try to reduce this enormous toll on families on society through better access to defibrillators? How do we make these more readily available?

Our study determined three options to disseminate more defibrillators across Australia.

Greg’s objective is to establish another 184,000 public access and household defibrillators in Australia.

If we have a community, say a small rural village, how do we know where the defibrillators are? How can we access them? Can we access them in three minutes?

Option one: increase public access to defibrillation for bystander access based on the Victorian data

The first option we proposed was a trial to be conducted in Victoria.

Our estimate of the number of defibrillators available in 2017/18 was 4,500 units. Some 30 lives were saved by bystanders using a defibrillator in Victoria that year.

Let’s say, in that year, we had 50 per cent more units available across Victoria, how many lives could we save now?

The important point to bear in mind is that we’ not talking about the number of live saved in one year. A single unit has a lifespan of around eight years, based on that technology.

Based on these numbers, we estimated around 300 more lives could be saved over the eight-year period.

Under this model, we worked out that for every dollar invested in a defibrillator, the return was approximately seven dollars.

Figuring in terms of current markets, this return represents a worthwhile investment. It gave us a good base to go forward to a second option.

Option two: establish pharmacy-based defibrillator networks

That second option was to consider a major pharmacy chain.

There are several reasons for this. You have many clients coming into a pharmacy seeking heart medication. Pharmacists have a very good reputation in their well respected, particularly in rural areas, and I think that sort of confidence in the pharmacy sector has been highlighted recently in terms of the distribution of the Covid 19 vaccine.

The pharmacy is a source of trust and know-how within the pharmacy to talk about defibrillation, explain how it works, and instil confidence throughout the community.

You also have a source of collection of units for maintenance, which is critical.

These units have to be maintained. Once you have an application, the pads have to be replaced. The battery normally has to be replaced halfway through the life cycle. The recommendation is that you replace the pads every two years, and have three sets of pads over a life cycle.

So, to us, pharmacy chains represent a good option in terms of how you could disseminate, maintain and give people the confidence in a defibrillator.

From here, how do we estimate the cost of disseminating defibrillators?

The cost of the 184,000 defibrillators based on Option One was about AU$1.8 billion. The estimated benefits, AU$3.4 billion. That gives you a benefit cost ratio of two.

Option three: national distribution model

The third option that we looked at was a full model developed by Greg Page’s Heart of the Nation, which included the acquisition and maintenance of a defibrillator network across Australia.

That model involves development of an app so that anyone coming into a town knows where there could be a defibrillator.

For me, that sort of app is essential in terms of community access and minimizing the delay in securing a defibrillator.

This is a more expensive model. The costs do go up quite considerably from the third-party pharmacy model, up to AU$2.7 billion.

As you increase the cost, in order to achieve a benefit cost ratio of two, the number of lives that you have to save over that eight-year cycle increases markedly.

Under this model, we would need to save a minimum of 333 additional lives each year, for a total benefit of approximately AU$5.4 billion.

That shows you how the orders of magnitude can change as you vary some of those key parameters.

Where to from here?

I think this approach clearly demonstrates what is doable under the different models and how we could achieve these sorts of outcomes for the benefit of the broader society.

For example, the availability of defibrillators in major office blocks, one per floor, would be a significant step forward.

We also have these developments now starting to take place in major retail malls in terms of access.

I think part of what we are saying here is the need for big players in society to step behind this and to help make it happen. It is an urgent need.

Sudden cardiac deaths represent a huge cost to society. Until we were asked to undertake this work, the magnitude of that cost hadn’t really been understood.

This work was put together to try and improve that understanding, and support what is a very worthwhile cause: the broader distribution of defibrillators, to the benefit of our society.

RELATED ARTICLE: Can we predict sudden cardiac arrest?