Cultural change requires early adopters

Are you reading this on a smartphone?

If you’d said yes to that question in 2007, chances are you were among the first to buy an Apple iPhone.

The iPhone wasn’t the first smartphone – but Apple was the first to introduce the touchscreen technology that went on to change how we think about telephony, computing, photography, media, entertainment, business and community.

This remains one of the best examples of how technology has fuelled cultural change – and how early adopters were integral to making that happen.

What is an early adopter?

An early adopter is someone who uses a new innovation before most others. They’re motivated to be first, and usually pay more, if it means the product improves their life or business, or raises their social standing.

Companies like Apple have grown on the back of early adopting fans of its brand and products. In addition to buying early and often, these fans are often also evangelists – helping build enthusiasm in broader markets.

That evangelism is what starts to bring about cultural change in relation to innovation.

Diffusion of innovation

Communication studies professor, Everett Rogers first published his theory of Diffusion of Innovation in 1962; it remains the most widely cited theory on consumer adoption of new innovations.

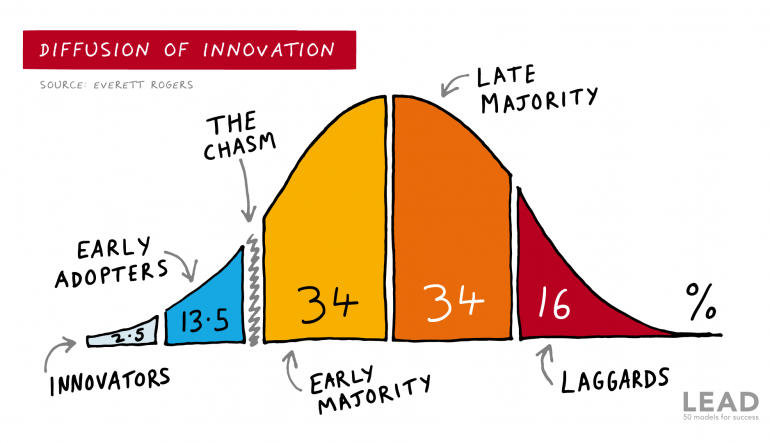

The Diffusion of Innovation model is represented by a bell curve (pictured) showing the stages of market adoption of a new product.

According to Rogers, any new innovation is first adopted by the innovators – that tiny minority of individuals who are miles in front of everyone else in terms of their understanding of the need, and possible applications for that product.

They’re closely followed by the early adopters, who have quickly caught on to the potential and want a piece of it.

For a lot of new innovation, that’s where the market opportunities end.

The Rogers model describes the chasm separating early adopters from the broader market. An innovation that is able to transition from being coveted by the converted, to becoming a mass-market consumable, has achieved what the vast majority of new products are unable to do.

According to Rogers’ original theory, there are five attributes that impact its adoption.

- Relative advantage – is the innovation better than what it’s replacing?

- Compatability – does the innovation recognisably build on what came before? Can I understand it?

- Complexity – is it easy to use?

- Trialability – can I experiment with it?

- Observability – are the results of this innovation clear for all to see?

The better an innovation meets these criteria, the faster its adoption.

Many studies have built on the original Rogers model, with suggested additions. For example, a more recent inclusion is image – how much early adoption of this innovation increases social standing?

Diffusion of innovation in medical technology

Do these rules apply to medical technology? Is it possible for med tech to jump the Diffusion of Innovation chasm?

Insulin pumps and hearing aids are two examples that suggest that yes, it can.

In these cases, the technology has solved a problem impacting a large proportion of the world’s population. The same could be said for sudden cardiac arrest.

For anyone trying to improve sudden cardiac arrest survival rates, the hope is that the same can be achieved for AEDs (automated external defibrillators).

AEDs have been available for decades, yet have never received mainstream adoption. Reasons include cost, difficulty of use, limited reliability and difficulties associated with making enough available to be effective in response to sudden cardiac arrest.

The real need is to have AEDs in homes, where four out of five out-of-hospital cardiac arrests occur.

For that to happen, innovative AEDs will need to meet the Rogers Diffusion criteria of being better, while still complementing existing systems for responding to emergencies; of being easy to use and demonstrably effective; and of being able to be rehearsed with.

Early adopters have been instrumental in cultural change around consumer and business technology. Can the same be achieved in the quest to improve community preparedness to respond effectively to cardiac arrest?

RELATED ARTICLE: The future of defibrillation isn’t science fiction